Vietnam Lunar New Year 2026.Between Two New Years in Vietnam: Life in the Long Wait for Tết - Part 1

Vietnam Lunar New Year 2026. A reflection on the "long January" in Vietnam, where the Western calendar says 2026 has begun, but the country remains in a "coiled" state, waiting for the Year of the Fire Horse.

CULTURE

Hein Lombard

1/12/20266 min read

Between two new years in Vietnam

I woke up on January 1st with ''Xuân Đã Về'', a popular Tết song, playing at full blast in the coffee shop next to my house in Sóc Trăng, and for a moment I forgot what year it was. Not hungover. Stranger than that. As if the year itself hadn't quite arrived. My phone said 2026. The Western world had already flipped the switch, posted its resolutions, and started sending emails with "Happy New Year" in the subject line. But outside, nothing felt new. Vietnam was still waiting.

The streets were quieter than usual. Not empty, just oddly restrained, like a town between seasons.

This is the strange stretch of living in Vietnam: the gap between two calendars, two countdowns, two completely different ideas of when a year actually begins.

Two Clocks, One Country

Vietnam runs on two clocks, and in early January you can feel both of them ticking.

There's the Western clock. January 1. Fresh starts. New goals. Back to work. Schools reopen. Offices switch their lights back on. Life is supposed to move forward because the calendar says it should.

Then there's the Vietnamese clock, which doesn't care about any of that. It waits for the second new moon after the winter solstice, somewhere between late January and mid-February, when Tết arrives and the lunar year turns. This year the Snake steps aside for the Fire Horse—Bính Ngọ—on February 17th. That's when the real reset happens. Debts get settled. Homes get cleaned. Ancestors are honored. That's when people actually feel the old year end.

Until then, everything is in a kind of pause. People are working, but not fully. Planning, but not committing. You hear it everywhere if you listen. "After Tết." Those two words act as a national pause button.

The Economic Coiling

This isn't just a mood. It's a massive economic coiling.

While the West spends January in a post-holiday slump, Vietnam is storing energy. For a lot of businesses, this thin month is followed by the biggest burst of the entire year. Right now, people are holding back because they know what's coming.

Tết is expensive. There are bonuses to pay—thưởng Tết, often a full month's salary or more—and red envelopes to prepare. If you're an employee, you're already mentally dividing that money between parents, kids, and whatever you need to survive the year ahead.

So January stays thin. Restaurants are open but not busy. Shops are running but not pushing. Everyone is saving their energy, and their cash, for what's coming. Vietnam isn't quiet. It's wound tight.

A Riverine Tapestry

Down near the river, the wet market is open. Fish on ice. Piles of greens. But half-loaded, like someone forgot to finish stocking it. No big fruit displays yet. No mountains of mandarins or red-and-gold decorations. That comes later.

By mid-January, though, the brown canals of the Delta start to change. The markets explode as the river becomes a moving tapestry. Thousands of wooden boats, loaded so heavily with yellow chrysanthemums and marigolds that their hulls sit inches above the water, drift toward the city centers.

You see the mai trees everywhere—yellow apricot blossoms, the iconic flower of Tết in the South. In a strange ritual of forced rebirth, gardeners strip every single leaf off these trees by hand weeks in advance. It looks like an act of destruction, but it's a calculated gamble to ensure a golden bloom on the exact day the Fire Horse arrives. Nearby, pink peach blossoms from the North are trucked in, kept cool against the Southern heat—trees from two different climates, both waiting for the same moon.

Shedding the Old Dirt

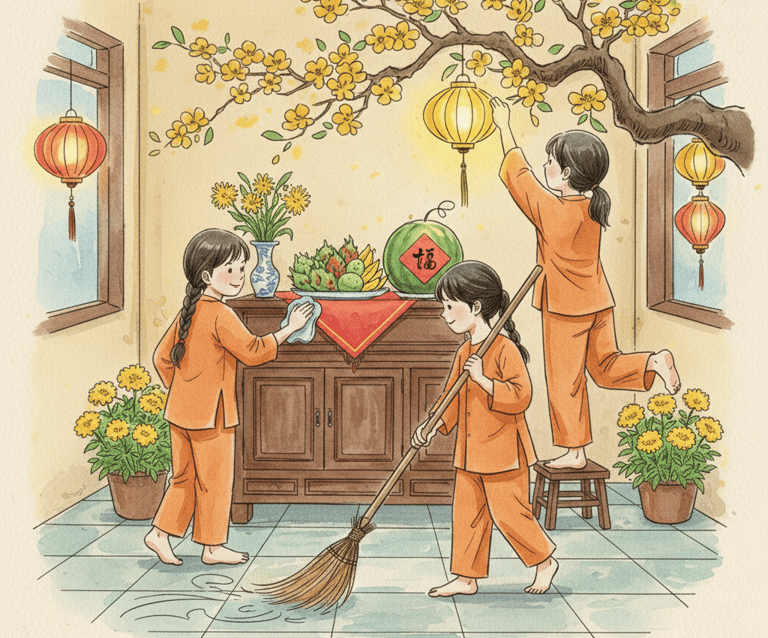

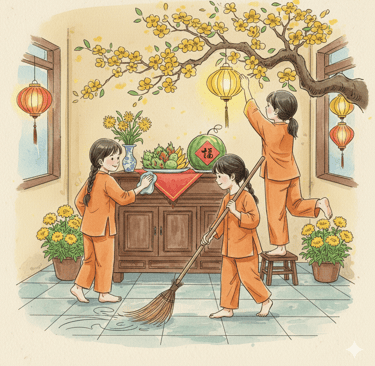

You start noticing the preparations in small, ordinary ways. My landlord spent an entire afternoon scrubbing the courtyard walls, working slowly from the roofline down. When I asked what was going on, he laughed. "Cleaning for Tết," he said. "You don't bring old dirt into a new year."

That idea runs deep here. You clean before Tết so you don't carry bad luck forward. Not just dirt, but unpaid debts, unresolved problems, unfinished business. Houses get washed. Walls get repainted. Altars get refreshed with fruit, incense, and offerings for the ancestors.

In most Vietnamese homes, that altar sits in the main room, watching everything. Photos of the dead. Bowls of food. Cups of rice wine. During Tết, the altar gets its own offering: the mâm ngũ quả, a five-fruit tray arranged with care. The fruits are chosen as a pun—cầu sung vừa đủ xài, "pray for enough to spend." During Tết, families gather there to pray and talk to the people who came before them. The past isn't abstract here. It's sitting in the room with you.

The Shadow of the Fire Horse

The country is already starting to lean toward it. Buses and ferries are running, but they're not full yet. That comes later, when millions of people pour out of the cities and head back to their home villages. Tết is the one time everyone is expected to return, no matter how far they've gone.

Right now, it's all still being planned. My students are distracted. Half the conversations I hear end with the same words: when Tết comes. Red lanterns have started appearing in shop windows. Just a few for now, like early warnings.

And then there's the Fire Horse. People are already talking about it. Not seriously, exactly, but it comes up. A shopkeeper laughs about it when something goes wrong. A teacher blames a noisy classroom on "Fire Horse energy." The Vietnamese zodiac pairs animals with elements—wood, fire, earth, metal, water. Twelve animals, five elements, sixty-year cycles. Fire Horse years are the wild ones. Strong. Restless. Hard to control.

It's not fortune-telling. It's more like a shared way of talking about what kind of year everyone expects to be walking into. A mood. A tone. A sense of volatility that everyone is bracing for. The Fire Horse hasn't even arrived yet, but you can feel it hovering in conversations, in the way people hedge their bets and talk about what kind of year this might be.

Culinary Alchemy

By mid-January, the stillness of the construction sites—where cranes stand frozen over half-finished buildings—is slowly replaced by something else. The crackle of wood fires on the sidewalks. The smell of banana leaves and pork fat.

This is the labor of the bánh tét.

Unlike the square bánh chưng of the North, the Southern bánh tét is a heavy cylinder of glutinous rice and pork fat wrapped in banana leaves. It's a twelve-hour commitment. You cannot rush a bánh tét any more than you can force the Fire Horse to arrive early. Families sit by these street-side cauldrons all night, a forced period of storytelling and vigilance. They are boiling away the old year, waiting for the pork fat to liquefy and bind the rice—the slow process that tells everyone the old year is really ending.

Workers have already gone home to get ready. "No one starts something big before Tết," a friend told me. "Better to finish the old year first."

The Comfort of the Wait

Living inside two calendars at once messes with your sense of time. My email inbox talks about Q1 goals and 2026 plans. But outside, nothing feels like it has really begun. Here, time runs in circles, not lines. It moves with the moon, not with spreadsheets.

Tết has been here longer than most modern borders. It outlived empires and wars and governments. And it still decides when a year truly starts, because it ties people back to family, land, and ancestors in a way no official holiday ever could.

So January drifts by. The lights are on, but no one's really ready. Even the air feels like it's waiting. January here is cool and dry, humidity stripped away, no rain for weeks. Kids show up to school in jackets and hats, some even wearing scarves in the morning. Everything feels paused, like it's holding itself back.

Living here teaches you that not everyone lives on your clock. The Western world says a year starts on January 1st. Vietnam doesn't. It waits. And there's something oddly comforting about that, about letting time arrive when it's ready instead of forcing it.

Soon the firecrackers will crack the air open. The coiling will release into a fever of red and gold. The streets will be jammed with motorbikes stacked with gifts. Families will crowd around altars at pagodas. The markets will be deafening.

But for now, Vietnam is still gathering itself. The country is cleaning its houses, boiling its rice, and waiting for the water to fill with flowers.

Not resting. Coiling. Waiting for the real new year to begin.

"The preparation is only half the story. Read Part 2: The Art of Stepping Aside to see where I go when the country begins to move.

About the Author

H. Lombard is a South African writer and educator currently living in Sóc Trăng, Vietnam. Nestled in the heart of the Mekong Delta, he spends the "gap months" between calendars observing the intersection of tradition and modern life. When he isn’t teaching or navigating the "Tết Tide," he is likely exploring the Delta’s back roads or heading toward the quiet coastlines of the East Sea.

© 2025. All rights reserved.

hello@gonomadnest.com